I ran into this question in an SF/F group: How do you create an alternate timekeeping and calendar system? I found it interesting because it’s not so much about comparing some local calendar to the one we use here on Earth, but about creating one from scratch. How do we do that?

I ran into this question in an SF/F group: How do you create an alternate timekeeping and calendar system? I found it interesting because it’s not so much about comparing some local calendar to the one we use here on Earth, but about creating one from scratch. How do we do that?

I figure it goes back to the most basic observable phenomena. The sun rises and sets. Seasons come and go. The moon waxes and wanes. Everything else is just invented units for bookkeeping. So how do we invent that bookkeeping?

Let’s look at the two most important units to primitive time keepers: days and years. These are almost certain to exist in any timekeeping or calendar system. If the people are in anyway diurnal (or their prey or predators are), then they’re going to keep track of days at least to the extent of yesterday, today, and tomorrow. If there is any travel, you are almost certain to make plans to pack provisions for five days rather than merely two days.

Likewise, the coming and going of seasons will affect the migration of game, the availability of certain plants, and the need to hunker down and stay warm vs. escaping the heat of summer, so years will also be tracked in some form, at least to the point of talking about a previous year’s seasons or next year’s season. You might not talk about years specifically, though, since times could be discussed as “three summers ago” or “I have lived through nineteen winters.”

But what about dividing up the day? The easiest division is day vs. night, but dividing that up into smaller units is somewhat arbitrary. We got out 24-hour clock by an early sundial method of dividing up the day into ten hours of sunlight, plus an hour of twilight at each end. This was mirrored over to night through the tracking of certain stars.

But what about dividing up the day? The easiest division is day vs. night, but dividing that up into smaller units is somewhat arbitrary. We got out 24-hour clock by an early sundial method of dividing up the day into ten hours of sunlight, plus an hour of twilight at each end. This was mirrored over to night through the tracking of certain stars.

Alas, depending on the time of year, these daylight hours varied in length, with long hours in the summer and short ones in the winter. This variation is fine in more primitive cultures, but once you start developing physics, you need a constant time measurement for talking about things like velocity and acceleration. So, sooner or later, that evolving society is going to have to nail down those hours into something rigid.

But ultimately the number of hours per day or the number of minutes/seconds/etc. is completely arbitrary. A metric division of time would be swell, but I’d have to question whether your timekeepers were that logical early enough to make it stick, rather than having sixteen hours a day because the gods willed it. The actual divisions could come from mythology to something as simple as counting the appendages on your alien or fantastical species.

As for the year, it is already naturally divided into days, but we seem to be primed to group them up into intermediate divisions like weeks and months. Certainly some of this is astronomical, and some of it is mythological, but a larger issue is that we have a hard time grasping bigger numbers at an emotional level. At some point, the distinction between 153 vs. 212 is lost on us while we can feel the difference between May and July in our guts. It’s hard to say for sure what an alien or truly fantastical brain is going to handle, but if their sense of time evolved along with spears and rocks, then it’s not going to have a lot of abstract math. And so we probably need at least some divisions.

The origin of our month comes from the more primitive cultures that tracked the passage time by the phases of the moon. This is believed to go back to stone age, but depending on how you want to observe it, there are several different ways to measure the moon’s orbit. Do you go by the phases, or do you see when it returns to the constellation of the squid? And what if you have two moons? Does one take precedence over the other? Or do you derive some time unit based on when the closer one eclipses the outer one? If there are three or more, do you look for some kind of regular alignment in their orbital rhythms? If there is no moon, there will probably be at least some demarcations of the seasons via the solstices and equinoxes.

The origin of our month comes from the more primitive cultures that tracked the passage time by the phases of the moon. This is believed to go back to stone age, but depending on how you want to observe it, there are several different ways to measure the moon’s orbit. Do you go by the phases, or do you see when it returns to the constellation of the squid? And what if you have two moons? Does one take precedence over the other? Or do you derive some time unit based on when the closer one eclipses the outer one? If there are three or more, do you look for some kind of regular alignment in their orbital rhythms? If there is no moon, there will probably be at least some demarcations of the seasons via the solstices and equinoxes.

Our seven day week is somewhat arbitrary and has as diverse origins as the Jewish creation story in Genesis and the astronomical observation of seven bodies that move through the sky (the sun, the moon, and five visible planets: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn). Various cultures have run on weeks ranging from three to ten days, and it’s probably as much the luck of history as it could be some seven-favoring internal wiring that caused us to end up with a seven day week.

But if you really want to go wild, consider some much stranger settings. Think about a species that lives entirely underground in caverns. There is no sky, so there is no day and night, no lunar months, not even solstices to mark the passing of the seasons and years. What do you have then? Is there an underground river that floods based on the seasons above? Is there a consistent geyser like Yellowstone’s “Old Faithful”.

Or think about a small ringworld, but instead of spanning an entire orbit like Niven’s Ringworld, make it only several thousand kilometers across and spinning around for gravity as it makes its ways around the local star. If its plane of rotation is tilted out of its orbital plane, it will still have seasons, but instead of the seasonal cycle taking the entire orbit as it does for Earth, they’ll have two sets of seasons per orbit. Consider a calendar with a first and second summers.

But, and this is a big one, I don’t like it when writers mess around with the calendar in a lame attempt to remind that we’re not in Kansas anymore. Certainly, I don’t require every epic fantasy to use the Gregorian calendar, but I remember the disaster of the original Battlestar Galactica’s use of “yarons” and “centons” for time keeping. It was overdone yet added nothing to the story. So if you’re going to mess around with the calendar, please have a good reason for it, please keep it in the background as much as possible.

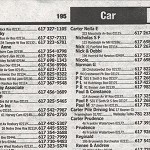

The second reference is the phone book. This is mostly useful for last names, as I’d like to avoid Mr. Smith as well as Mrs. Gnorpthrk. However, it’s sometimes tricky to pick out an ethnically appropriate last name from the phone book, but some googling for “Polynesian surnames” or the likes will get you a lot.

The second reference is the phone book. This is mostly useful for last names, as I’d like to avoid Mr. Smith as well as Mrs. Gnorpthrk. However, it’s sometimes tricky to pick out an ethnically appropriate last name from the phone book, but some googling for “Polynesian surnames” or the likes will get you a lot. And why should it matter that they’re pronounceable? After all, aren’t some alien mouths capable of making sounds we can’t even strangle out? Well yes, they can, but that’s not the point. The point is the readers have to care about these characters, and it makes it that much easier if their names can ring in the readers’ ears. Otherwise, the tragic love story of Xgrthum and Nzkla becomes that sappy tale about that X-dude and the N-chick on the distant world of I-don’t-give-a-crap.

And why should it matter that they’re pronounceable? After all, aren’t some alien mouths capable of making sounds we can’t even strangle out? Well yes, they can, but that’s not the point. The point is the readers have to care about these characters, and it makes it that much easier if their names can ring in the readers’ ears. Otherwise, the tragic love story of Xgrthum and Nzkla becomes that sappy tale about that X-dude and the N-chick on the distant world of I-don’t-give-a-crap.

I ran into this question in an SF/F group: How do you create an alternate timekeeping and calendar system? I found it interesting because it’s not so much about comparing some local calendar to the one we use here on Earth, but about creating one from scratch. How do we do that?

I ran into this question in an SF/F group: How do you create an alternate timekeeping and calendar system? I found it interesting because it’s not so much about comparing some local calendar to the one we use here on Earth, but about creating one from scratch. How do we do that? But what about dividing up the day? The easiest division is day vs. night, but dividing that up into smaller units is somewhat arbitrary. We got out 24-hour clock by an early sundial method of dividing up the day into ten hours of sunlight, plus an hour of twilight at each end. This was mirrored over to night through the tracking of certain stars.

But what about dividing up the day? The easiest division is day vs. night, but dividing that up into smaller units is somewhat arbitrary. We got out 24-hour clock by an early sundial method of dividing up the day into ten hours of sunlight, plus an hour of twilight at each end. This was mirrored over to night through the tracking of certain stars. The origin of our month comes from the more primitive cultures that tracked the passage time by the phases of the moon. This is believed to go back to stone age, but depending on how you want to observe it, there are several different ways to measure the moon’s orbit. Do you go by the phases, or do you see when it returns to the constellation of the squid? And what if you have two moons? Does one take precedence over the other? Or do you derive some time unit based on when the closer one eclipses the outer one? If there are three or more, do you look for some kind of regular alignment in their orbital rhythms? If there is no moon, there will probably be at least some demarcations of the seasons via the solstices and equinoxes.

The origin of our month comes from the more primitive cultures that tracked the passage time by the phases of the moon. This is believed to go back to stone age, but depending on how you want to observe it, there are several different ways to measure the moon’s orbit. Do you go by the phases, or do you see when it returns to the constellation of the squid? And what if you have two moons? Does one take precedence over the other? Or do you derive some time unit based on when the closer one eclipses the outer one? If there are three or more, do you look for some kind of regular alignment in their orbital rhythms? If there is no moon, there will probably be at least some demarcations of the seasons via the solstices and equinoxes. But I didn’t feel like the story had actually started. Instead, I had half a dozen story lines that did not seem to connect at all except that the character in scene fourteen was apparently the mother of the guy in scene nine. In fact, the only character I saw twice was really just one scene broken into two pieces a mere fifteen minutes apart.

But I didn’t feel like the story had actually started. Instead, I had half a dozen story lines that did not seem to connect at all except that the character in scene fourteen was apparently the mother of the guy in scene nine. In fact, the only character I saw twice was really just one scene broken into two pieces a mere fifteen minutes apart. I think this has always been true, but it’s true now more than ever: You need to hook the reader early. How?

I think this has always been true, but it’s true now more than ever: You need to hook the reader early. How?