Today is the 43rd anniversary of Apollo 11’s landing on the moon. There’s nothing magic about the number 43, but it’s the first time it’s rolled around since I started my blog. Apparently, that’s enough for me to get my soapbox out. So, this is me, getting up on that soapbox:

The space race, from Mercury through Apollo, made science cool. It wasn’t all white-coats, beakers, and blackboards. It was fiery rockets going to fantastic places. It was making maps and looking over the horizon. Fill up that extra oxygen tank, Sparky, because we’re heading out in the morning!

The space race, from Mercury through Apollo, made science cool. It wasn’t all white-coats, beakers, and blackboards. It was fiery rockets going to fantastic places. It was making maps and looking over the horizon. Fill up that extra oxygen tank, Sparky, because we’re heading out in the morning!

Now science seems to be about smaller computers, cosmological models, new materials, and better batteries. Even something as cool as the discovery of the Higgs boson fails to connect with the common man. More to the point, it fails to connect with the common kid.

I was born in 1967, and while I don’t remember it, I’m told I was on my daddy’s knee when Neil Armstrong took that one small step. My older brother remembers more of the space race, but I still grew up knowing that men were going up to the moon and doing stuff there.

I was born in 1967, and while I don’t remember it, I’m told I was on my daddy’s knee when Neil Armstrong took that one small step. My older brother remembers more of the space race, but I still grew up knowing that men were going up to the moon and doing stuff there.

I watched the final return from Spacelab on my grandmother’s TV, and I saw the launch of Viking II from the balcony of a Florida motel. And in a curator-curdling act, I stretched my little arm past the velvet rope and touched the Apollo 11 capsule in the Smithsonian. This was not some vague extrapolation of the Standard Model of particle physics. It was something I experienced in a very real and visceral way.

So, of course, I wanted to be an astronaut. At the age of seven, I did not really know what that entailed, but I knew that all this stuff about going into space required scientists, engineers, and mathematicians. So studies of English, social studies, and other soft stuff fell by the wayside as I pushed myself into whatever I could find that was at least a little scientific.

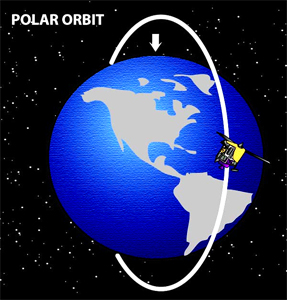

Ultimately, I found my proficiency for math and computer programming, and while I never even tried for a job at NASA, I did end up writing software used to design many of the vehicles that have been launched into space in the last two decades. It was also used to design bridges, houses, planes, and computers, but it was not the notion of writing useful design software that sparked my interest as a kid. It was the bold adventure of heading off into space. Even now, I hold out some tiny hope that I might someday make it at least into orbit on some tourism venture.

Ultimately, I found my proficiency for math and computer programming, and while I never even tried for a job at NASA, I did end up writing software used to design many of the vehicles that have been launched into space in the last two decades. It was also used to design bridges, houses, planes, and computers, but it was not the notion of writing useful design software that sparked my interest as a kid. It was the bold adventure of heading off into space. Even now, I hold out some tiny hope that I might someday make it at least into orbit on some tourism venture.

People debate about the costs and benefits of the old space race. The cost blew through all estimates, and the quoted benefits are often limited to such mundane things as velcro and tang. A deeper look adds advances to such fields as computers, telecommunications, and material sciences, but even with those we face the argument that we could have achieved those advances with earth-bound research initiatives at a fraction of the cost.

But what people rarely talk about is that going to the moon made science cool to millions of kids like me. My story of spaceflight inspiration is hardly unique in my generation, and while only a fraction of us went on into the so-called STEM fields (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics), a lot of us did. I haven’t been able to lay my hands on the actual numbers, but I’ve seen a few graphs to suggest that the percentage of US bachelor degrees in STEM fields peaked in the mid-80’s and has been in decline ever since. In other words, that surge in the percentage of STEM graduates was from that generation of kids who grew up watching Neil Armstrong walk on the moon.

These days, there is a lot of talk about increasing the number of STEM graduates here in the US. We’re told we need it to remain competitive in the global economy. Proposals abound on how to fix this, and they’re all about education reform, industry involvement, and tuition incentives.

Yet I haven’t heard a single proposal about inspiration. No one is talking about lighting that fire to make kids want to explore science in the first place. That’s not a decision we make when graduating high school. It’s not even a decision we make when we’re going into high school. I think that decision is made somewhere deep inside when we’re seven or eight years old. It lights a fuse inside, and it keeps us going until we’re blowing up chemistry labs and crashing mom’s computer.

Yet I haven’t heard a single proposal about inspiration. No one is talking about lighting that fire to make kids want to explore science in the first place. That’s not a decision we make when graduating high school. It’s not even a decision we make when we’re going into high school. I think that decision is made somewhere deep inside when we’re seven or eight years old. It lights a fuse inside, and it keeps us going until we’re blowing up chemistry labs and crashing mom’s computer.

Meanwhile, humans heading out past Earth’s orbit has become something we talk about with nostalgia. Kids don’t see it happening on TV. It’s in old movies with retro music and in conversations between adults that begin with “Remember when…” The only time politicians talk about renewing manned exploration of the heavens, it’s always an initiative to bear fruit in eight to twelve years, i.e. long after we’ve forgotten the promise and when it has become the next guy’s problem.

Meanwhile, humans heading out past Earth’s orbit has become something we talk about with nostalgia. Kids don’t see it happening on TV. It’s in old movies with retro music and in conversations between adults that begin with “Remember when…” The only time politicians talk about renewing manned exploration of the heavens, it’s always an initiative to bear fruit in eight to twelve years, i.e. long after we’ve forgotten the promise and when it has become the next guy’s problem.

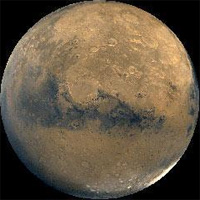

So, here’s my idea. Yes, do what we can to make science education better, but do something to spark that fire in little kids. This is not a solution for boosting STEM graduates in ten years. It’s probably won’t even help much in fifteen or twenty years. But if we step up and send people to Mars in ten years, it would produce a generation of scientists that would put my own generation to shame.

If you want more scientists, do something to make science cool again. Go to Mars and do more than leave a boot print.

If you want more scientists, do something to make science cool again. Go to Mars and do more than leave a boot print.

Given how little we see of our vast oceans, mermaids would have an easy time hiding out. They might even enjoy teasing our submarines. Centaurs and ents would find suitable homes in our forests, and the ents might even talk a few developers out of their plans. Basilisks would hunt as easily as dragons, and unicorns are well known for their invisibility to all but virgins. If I’m to believe the statistics, they should be safe as long as they stay away from grade schools.

Given how little we see of our vast oceans, mermaids would have an easy time hiding out. They might even enjoy teasing our submarines. Centaurs and ents would find suitable homes in our forests, and the ents might even talk a few developers out of their plans. Basilisks would hunt as easily as dragons, and unicorns are well known for their invisibility to all but virgins. If I’m to believe the statistics, they should be safe as long as they stay away from grade schools.